"The Transfiguration" by Fr. Chris House

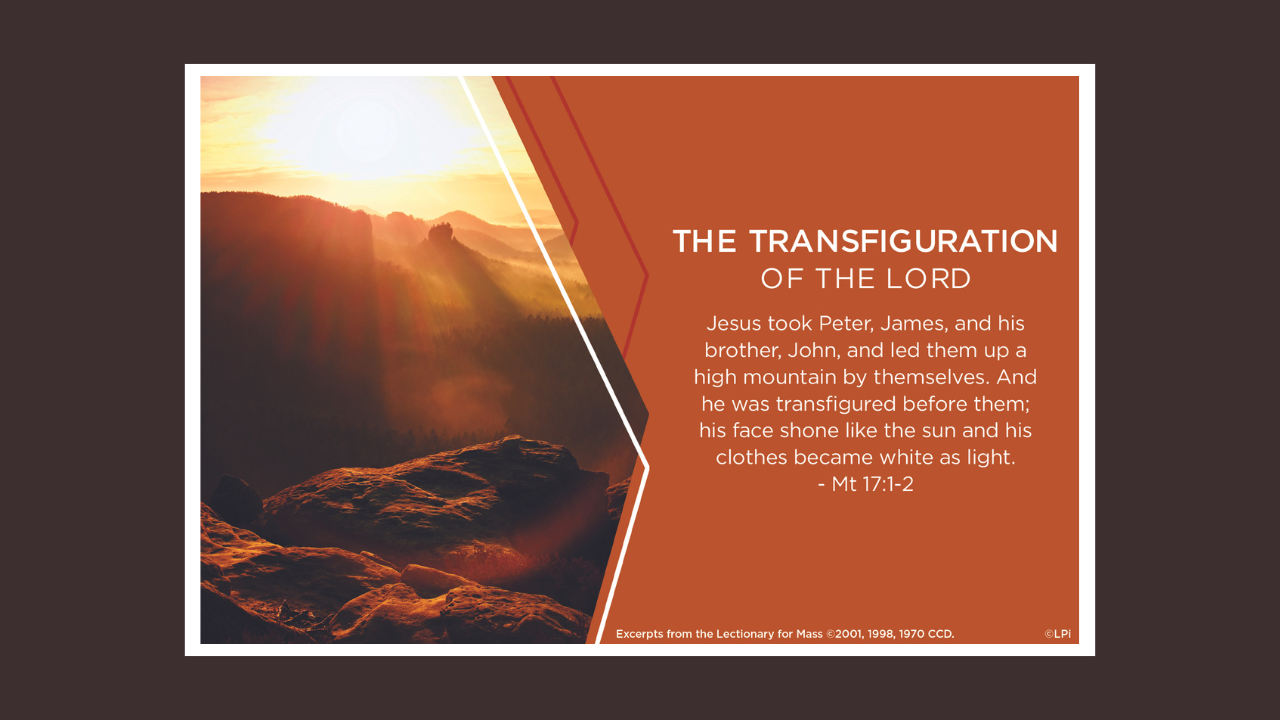

The Transfiguration calls us to embrace the Divine. Just as the disciples were astonished by the radiant transformation of Jesus, we too must open our hearts to encounter God in ways that surpass our understanding.

The Transfiguration

This Sunday finds us breaking from the green of Ordinary Time as the Feast of the Transfiguration, August 6th, falls this Sunday. The Gospel account of the Transfiguration should be somewhat familiar because, apart from August 6th, the story of the Transfiguration is recounted each year on the Second Sunday of Lent.

The Transfiguration calls us to embrace the Divine. Just as the disciples were astonished by the radiant transformation of Jesus, we too must open our hearts to encounter God in ways that surpass our understanding. The event on Mount Tabor reminds us that Jesus is not merely a great teacher or prophet, but the Son of God, the promised Messiah. In our busy lives, it is crucial to set aside time for prayer and reflection, seeking moments of spiritual renewal and allowing God's light to illuminate our hearts. Through prayer and contemplation, we can experience a personal encounter with Christ, drawing us closer to the divine reality that sustains our faith.

The Transfiguration reminds us of the importance of listening to God’s voice. As the disciples stood in awe, a voice from the cloud said, "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him." In our journey of faith, we encounter various distractions and conflicting messages that can lead us astray. However, God calls us to focus our attention on Christ, the Word made flesh. By attentively listening to His teachings, we gain insights into living a life of love, compassion, and justice. As we follow Jesus' example, we become bearers of God's light, radiating His love to the world and becoming agents of transformation in our communities.

The Transfiguration prepares us for the crosses and challenges of life. After the extraordinary experience on Mount Tabor, Jesus instructs his disciples not to speak of it until He has risen from the dead. This instruction points to the coming crucifixion and resurrection, reminding us that the path of discipleship many times involves moments of hardship and sacrifice. Just as Jesus willingly faced the Cross, we too must embrace our crosses with faith, trusting that God's glory will be revealed through our trials. In times of darkness, let us remember the glorious Transfiguration and find solace in the hope of Christ's resurrection, knowing that through our struggles, we are united with Him and participate in the triumph of eternal life.

As we contemplate the Transfiguration of our Lord, may we be inspired to seek God's presence in our lives, listen to His voice, and embrace the challenges of our earthly journey with unwavering faith, until the glory of the Lord is fully revealed.

Welcome Reception for Mrs. Jill Seaton

Next Sunday after the 8am and 10am Masses there will be a welcome reception for our new principal, Mrs. Seaton, in the parish hall. All are invited to come for fellowship and to welcome Mrs. Seaton as she begins her ministry as school principal here at CTK.

Blessings to you and yours for the week ahead!

Father Chris House